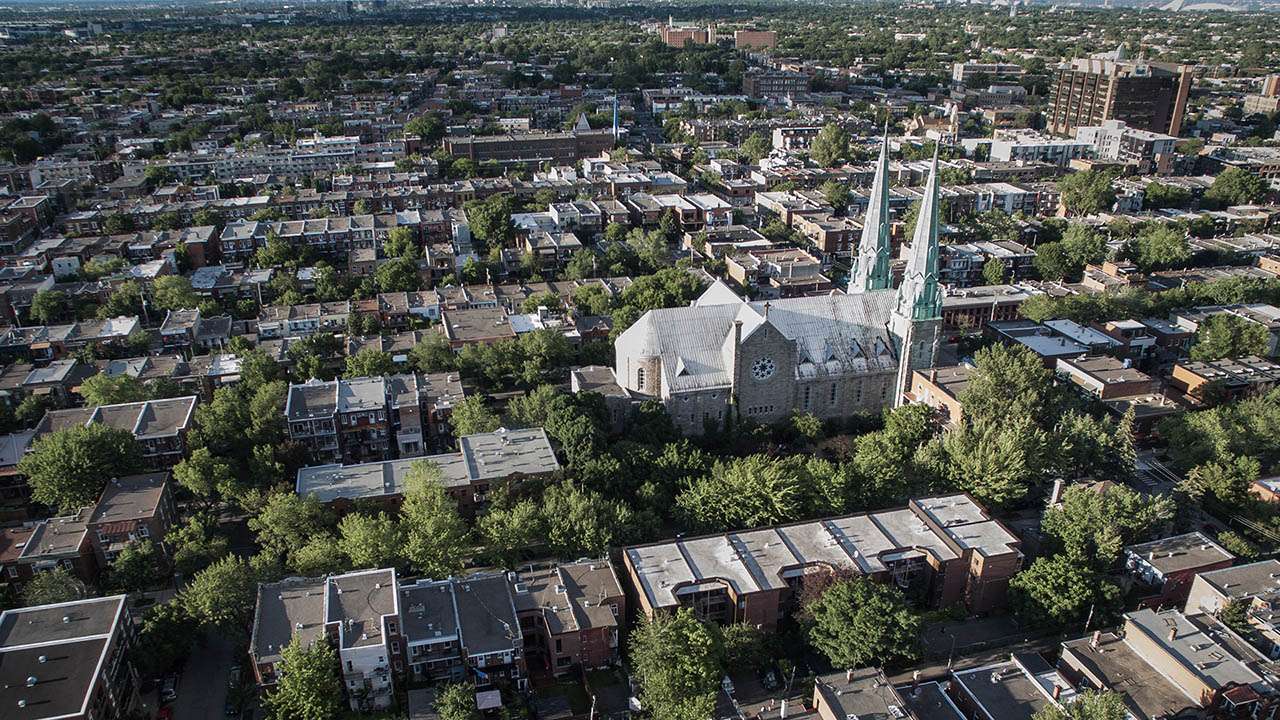

Recently, I was talking with a pastor who leads a church in Washington, D.C. I asked him how things were going, with all that shake-up in politics happening right now serving as the question underneath my question. He knew what I was asking. “Well, we have DOGE people and USAID folks who both come to our church,” he said.

My eyes widened, and I chuckled a nervous chuckle. The divisions so many churches across the country have faced the past few years have been massively destabilizing. But listening to this pastor, I was reminded that shepherding in places like D.C. means that people don’t merely hold different political views, but that these views are embodied in their daily work, as they actively labor for ends that are in deep conflict.

The pastor pondered what his role might be in all this. He recalled a series of gatherings the church had held for the congregation in the years before the coronavirus pandemic. They would host a conversation for congregation members around a polarizing topic and model civil discourse. Then, afterward, they would all take communion together, hearing those pride destroying words, “His body, broken for you. His blood, shed for the forgiveness of your sins.”

My mind raced to the subversive power of the Lord’s table. In the upper room, soon before Jesus would be betrayed, fierce political adversaries observed the Seder meal together — former financial beneficiaries of the Roman government with zealots who wanted to overthrow Rome. Jesus had assembled a group of followers who despised each other’s politics, and whose labors had been tied up with those views. His broken body and shed blood would mean that human categories of division would be superseded by their identity in Christ (Gal 3:28-29).

But does this amount to religious sentimentality that glosses over deep differences? That in the new heavens and new earth, the lion and the lamb will lie down together is not in doubt. But what about the donkey and the elephant, in our day and time? After all, as William Cavanaugh has argued in Migrations of the Holy, religious fervor hasn’t decreased in the past few decades, but merely migrated to the realm of politics. How does the New Testament address political affiliations?

There is no doubt that Jesus’ self-disclosure as “Lord” was profoundly political. Decades before Jesus’ public ministry, Herod knew that Israel’s Messiah was a threat to his throne, and so he tried to wipe out Jesus by killing all the young children two years and younger. And yet, when that same Jesus grew up, he rarely spoke of Rome, and neither do the other writers of the New Testament.

The closest thing you hear to outright prophetic political critique is in Revelation, which makes a veiled but devastating denouncement of Rome (“Babylon”) by referring to its evil brutality as “the beast” and its wicked economy wooing people with the promise of prosperity as “a harlot.” But Nero or Domitian are not mentioned by name, as if they are small, insignificant players in God’s great drama — like large logs in a fast moving river — imposing, but soon to be thrown over the edge of the waterfall.

Meanwhile, it is not the mighty government but the church, or rather, churches, who are named, and given political promises by Jesus (Rev 2-3). “To the one who is victorious and does my will to the end, I will give authority over the nations—that one ‘will rule them with an iron scepter and will dash them to pieces like pottery’—just as I have received authority from my Father” (Rev 2:26-27).

Churches proclaim the audacious hope of victory, promised to those who do Jesus’ will to the end; and though it boggles my mind, the authority to rule over the nations with Jesus. He holds this right not by democratic election, or an autocratic takeover, but by being the “Lamb, looking as if it had been slain” (Rev 5:6), and his followers hold this right, not through campaigning, but by bowing their knee to him.

Which brings us back to the Lord’s table. Can a meal of remembrance, instituted by Jesus 2000 years ago, reconcile those who work for DOGE and U.S. Agency for International Development? I don’t know. Humanly, it is hard to fathom. But the church isn’t called to weigh the odds and choose the most likely path of success.

It is called to gather God’s people, and offer his broken body and shed blood, telling us that we are sinners saved by grace. We believe this humble meal does its slow sanctifying work in us as we chew and drink a prophecy of our ultimate political future, for “as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” Maranatha.